It’s the late 2000s, video games are more mainstream than ever before and no matter what your taste happens to be there’s a genre waiting for you to explore. Unless you were into horror games, that is. For a series that had made its bones with the likes of Silent Hill, Alone in the Dark and Sanitarium, horror had eventually fallen out of fashion in an industry that was more focused on creating summer action blockbusters.

And then Dead Space came along. EA and Visceral’s humble sci-fi horror experience reignited the genre, set a new benchmark in terror and thrilled fans with its nightmarish visuals. It also helped that Dead Space had an amazing sound, a soundtrack of chills provided by composer Jason Graves. That eerie collection of audio would go on to define the series long after its debut, resulting in Graves becoming Dead Space’s soundtrack architect over its two sequels and spin-offs.

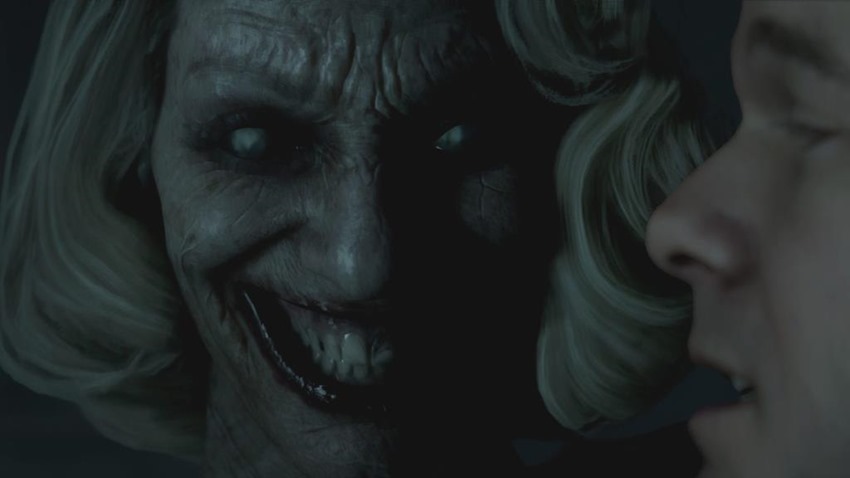

Since then, Graves’ contributions to video games have resulted in some of the greatest soundtracks of multiple generations and franchises. From Dead Space to Tomb Raider, The Order: 1886 and Lawbreakers, Graves is still the go-to composer for a horror game. He’s recently been doing a lot of work in that genre as well, contributing to the creeptastic score of The Dark Pictures Anthology and outside of it, DC Universe’s ill-fated Swamp Thing.

I had some questions for the music-wizard about how he created the sound of horror, and Graves was only too happy to wax lyrical about finding his groove, the sheer genius of how his music was used and the power of psychology.

I’ll be the first person to say that it’s an absolute crime how your soundtrack for Blazing Angels: Squadrons of WWII doesn’t get more love, but how did you find yourself in the position of the go-to guy for music in horror video games?

I think the short answer to that is a combination of my background, sheer coincidence and timing. I have an undergraduate degree in music composition but my professor was very avant-garde and more John Cage than John Williams. When I first started working on my first big horror game, which was Dead Space, I was just doing what sort of came natural and doing very aleatoric kinds of things.

Dead Space was a hit, so you combine that with the fact that my last name is “Graves” and you’ve pretty much just cemented a lifelong association with scary music. Which is totally fine! I love writing scary music.

If you had to look at the era in which Dead Space was launched, that was a time when horror games were thought to be dead. I don’t think anyone realised just how big Dead Space was going to be when it launched, but post launch it’s the Street Fighter 4 of its genre: It basically made horror games mainstream again. You were coming off of game projects like Flushed Away, Transformers and Star Trek Conquest. What was it about Dead Space, that you wanted to sign up for this game? And how was it seeing the post-launch reaction to a game that was so celebrated at the time?

Well it was a small team that made the game. There were only a real handful of us in the beginning and I was involved for more than two years before the game came out. I had a lot of hands on experience playing the game, there were so many trips out to EA to talk about it and play the game there. It was a very personal experience but what really drew me to it in the beginning was that it was everything that I had been doing before.

I lot of the titles you mentioned, were existing intellectual properties. A game based on a movie or a game based on some toys. That was sort of the everyday gig for me at the time, I was still relatively young. I’d been working for five years and this was the first original game where there were no expectations for what the music needed to be. EA really let me do whatever I want. They just said they wanted it to be really really scary.

I could have done death metal with screaming and post-apocalyptic industrial guitars. You could have gone a thousand different ways with it. It just happened that my classical leanings made sense to make it orchestral.

Do you find that putting yourself in a certain headspace and atmosphere helps with how you compose music in this genre? Does it help to juxtapose the isolation of working on your own in your office with the sense of dread that a player will feel when they’re exploring an environment in games such as Dead Space or the Dark Pictures Anthology?

By the time I was about two thirds of the way through for the making of the soundtrack for the first Dead Space, I had gotten so beaten up psychologically by the process of trying to do the best job I could. This music is not something you’re going to put on if you have some folks over for a couple of beers. It’s very unpleasant, it’s intentionally unpleasant.

If it’s hard for you to sit and listen to a four minute track of this orchestra, imagine me spending a day writing that track! I was becoming immune to the fear factor of everything, so as a result I kept ramping everything up to be scarier. The last third of the soundtrack was just crazy over the top insanity. When I was building the original soundtrack, taking all the cues from the game and making the Dead Space album, I was so over it by then and I remember thinking ‘I’m just going to get this out the door, because no one’s going to want to listen to this!’

This is just scary over the top dissonant…everything. All the things that I thought of, the reasons why people wouldn’t like it, it turns out those were the exact reasons why people did like it. It was like ripping apart an orchestra. I thought of how I could Necromorph the orchestra. I was shocked when the music got me attention. I knew the game was good, I knew it was a good horror title and I thought it would show up on the radar as something original. I had no idea that the music would get the reception that it did.

Sometimes I can do stuff outside of the studio that helps inspire me. Normally it would be visiting the developer…so we’re still inside. It’s the plight and curse of any composer. Unless you’re John Williams and you’ve got your piano on the movie set, pretty much every other composer in the world is confined to a room by themselves. It’s pretty easy for me to get into the correct headspace. I’ve never been a slave to moods, I’ve always been a slave to deadlines, so for me, it’s like ‘it’s eight in the morning, the birds are singing let’s write some horror music!’. That’s what’s on the agenda for that day, it’s jump in and do it. And hopefully have fun and learn something along the way.

If I compare TV to video games, I can only imagine how challenging it must be to create that sense of mystery and fear. What happens on TV happens. You the viewer have no control over what’s about to occur, but in a video game it’s an interactive experience and the music has to shift with the player and their actions. So how challenging is it to not only compose a soundtrack for a game, but to provide hours of content that has to suit the action unfolding on the screen?

It’s a lot more straight forward doing TV. I did Swamp Thing with Brian Tyler. That was mostly horror, it was a limited number of minutes for music. You knew how many minutes you were writing, you knew how long it was going to be. With something like Dead Space, Don Veca the audio director had a lot to do with how successfully the music is integrated into the game.

Veca was also the one putting the music in, he created something in the game engine that EA was using. A proprietary piece of software that they were using just for music for originally just for their Godfather game. And then Dead Space was the next one that tried it. It made the interactive nature a little more straight forward because they would put a marker, Veca called it a fear emitter, on anything in the game. It could be a character, it could be a door, it could be a spaceship. The closer that you got to that fear emitter, the higher the fear.

It would ramp up the music automatically. I wasn’t even doing anything, I just provided four different layers of fear. From ‘you’re only the tiniest bit afraid’ to ‘you’re completely scared out of your pants’ and then the music system would turn the fear up as you got closer to that fear emitter. And it would work great! If you were on a long hallway and there was a fear emitter on the door, the music would start building…and building…AND BUILDING.

You’re getting to reach out and the music is just going crazy, and if you turned around and walked away the music died back down. It’s really seamless because with horror, there are no rules with music. You can make it crazy dissonant, tempo in different keys to make it scarier. It’d be more difficult to try and do that with a romantic piece of music. Because then you’re locked into the rules of music.

That’s what I love about scary music, because you can throw the rulebook out and do anything you want. As a drummer originally, that was very appealing to me. All the stuff I didn’t know originally, I can now extrapolate on. I can just be visceral and primal on how the music reacts when it’s meant to be scary.

So coming off of projects like the Dead Space trilogy, Fear 3 and Until Dawn, and then starting work on The Dark Pictures Anthology, do you feel like you’ve got a grasp on what the primary sound of horror is? Do you have a handle on what it takes to make your audience feel a constant sense of dread?

I have a rulebook in my head of what could be considered scary. But it’s no longer scary to me because I’ve heard it so many times. With that first Dead Space, becoming insensitive to the scariness, I always feel like I need to ramp it up a little more when the next game comes around. I think any artist is always trying to learn new things, break new ground and try to keep themselves entertained. There’s a groundwork of do’s and dont’s that I would definitely follow. Especially in terms of how the music would play in the game.

But other than that, everything else is really based on the game itself. That’s why it was so much fun to work on something like Until Dawn and not have it sound exactly like the score to Dead Space. Until Dawn, it’s on a mountain, it’s winter time, there’s people and supernatural elements. But Dead Space is sci-fi, it’s horror, it’s everything.

It’s fun contrasting those with each other and still following those rules that you mentioned. There’s always good ways to scare people! That will never stop I think. There’s all kinds of great jump scares, building terror and the whole idea of going against what you would expect the music to do. So if you’re expecting it to be this pretty chorus, you throw a couple of wrong notes in there, eyebrows go up and people start to get a little sweaty. They can’t figure out, but it’s because it’s just wrong. The music is wrong! And you know it in your soul even if you don’t anything about music. Short answer: Yes there are, but I always try to keep it different if I can.

I’m pretty sure that every instrument (except for a kazoo), can be scary in the right hands. That being said, are there any instruments that you’ve found to be particularly frightening? What delivers the best audio thrills and chills in your opinion?

It’s always the strings, or you could say its the violins. You’ve got more instruments if the instruments are quiet. Trumpets are really loud, you only have two or three of them in the orchestra. Violins are quiet and you’ll have twenty of them! And the reason I say that they’re scary is because it means that you have twenty players playing twenty different notes, twenty different things. You can break all those musical rules multiplied by twenty and imediately it’ll start giving you goosebumps because there’s so many crazy things that you can do with that.

As far a a single instrument goes, I would probably say that either a Bosphorous cymbal or maybe a waterphone, which is…bode metal. Actually let me revise: The single scariest instrument would be the Aztec death whistle. They look like little skulls and when you blow it, they sound like the most terrifying sound you’ve ever heard.

What’s the experience like for you though, to be constantly immersed in a world of horror when you’re working on these soundtracks? Do you find yourself desensitised and in need of a reminder of what it feels like to be scared so that your score can have that necessary psychological edge?

I have to cleanse the palette, so to speak. One of my biggest crimes that I probably do on every single track, especially if it’s a horror game, is I throw too much into the mix. It’s almost like a pizza that has twenty different toppings on it and you can’t really tell any of them apart from each other. It just has this weird flavour. I would do that that, I would put too many things in because it needed to be louder, it needed to be scarier.

Usually that’s in the afternoon, and I take a break. And then I do have the privilege of going outside, walking around and maybe going to the backyard and visiting all the animals out there. I take a 30 minute break and when I come back I hit play and it’s like okay! This is enough material for four pieces of music, we need start stretching this out a bit so that you can actually hear some of these things that are going on. It’s easy to feel insecure about what you’re working on and just piling more stuff on top of it.

It’s our human nature kicking in and telling us to put more on top and it’ll be great. Even outside of horror music, it’s always important to stay fresh and keep an open mind.

Is there a trick to crafting a score that can deliver a proper pants-shitting fright? Because I know that if I hear the music pace begin to increase, something is coming and I start to prepare myself for a jump scare. How do you avoid the obvious fright with this genre of music so that you can deliver something more unique?

If we’re going to be talking about horror stuff, I’m going to be talking about Don Veca a lot because he was the audio director on Dead Space. What Veca said then, that I still think about today, is that it’s all about the build-up to the boo. The “boo” is when you jump and throw your controller across the room. You can have a jump scare, it can be real quiet for a second and then there’s a flash on the screen and the music goes “BAH!”, it makes people jump. But that’s not the best kind of scare.

The best kind of scare is when you build up to it and that hallway that we were talking about before, is the perfect example. The music is building and you’re not even seeing anything. You’re just walking down the hall and psychologically, your fight or flight instincts have kicked in. The music has told you that something is wrong and you’re anticipating that something bad is about to happen.

I know something is going to be on the other side of that door, and I remember that Don said that he wanted the music to work in such an effective way that it would build up to that boo, get so intense that you could literally just have a fluffy white bunny rabbit hop out from behind the door and people would still scream! It’s all about the psychological tension that leads up to it. It’s all about The Shining instead of Friday the 13th. Psychology I think, goes a long way.

Last Updated: June 30, 2020